Guest Post: SFFILM Rainin Grantee Gerry Kim on the Complex Journey to the Screen for ‘I’m No…

by Gerry Kim

Guest Post: SFFILM Rainin Grantee Gerry Kim on the Complex Journey to the Screen for ‘I’m No Longer Here’

STORIES WITHOUT BORDERS

by Gerry Kim

Personally speaking, filmmaking has always been an extraordinary exercise in stamina. Pushing through long stretches of rejection while maintaining optimism and confidence for your project requires an obvious passion for the material. The process also requires a safety net of collaborators that you can trust, especially because of the inordinate amount of stress that can easily unwind a delicately constructed production plan — a production plan that often relies on unpredictable schedules hinging on highly combustible financing. I’m No Longer Here was a particularly ambitious undertaking since its story focused on an idiosyncratic, countercultural movement using a cast of mainly non-professional actors, told across two different countries.

Embarking on an Odyssey

I’m No Longer Here, a film that was supported by the SFFILM Rainin Grant, took over seven years to make. It began as a short story that my director, Fernando Frias de la Parra, wrote to express his interest in a unique countercultural movement (Kolombias) that emerged around the socioeconomic fringes of Monterrey, Mexico. It was an area that experienced one of the worst bouts of cartel violence in the early 2010s, but rather than tell another story about the drug war, Fernando chose to write about the transience of youth through the lens of dance and music. It was a story that also expressed the importance of home and community, finding joy and color in an area plagued with political instability and violence. Fernando and I were working together on a commercial shoot in 2013 when he first told me about the project, and as our conversations and friendship evolved, I knew that I wanted to be a part of the film.

Though I’m No Longer Here told the story of a Mexican teenager that faced forced migration into the US, I somehow felt a strong connection with the material. Loneliness and alienation, and the awkward attempts to re-create a facsimile of home in a new country were themes that I witnessed firsthand with my parents, who left a post-war Korea for the United States. They barely spoke English and had no familial connections in Chicago, and I saw their attempts to assimilate into a country where they didn’t quite belong. Although Fernando’s story felt very specific and singular to Mexico, it also carried an emotional resonance that felt heartbreakingly familiar, and I strongly felt it was an essential piece of the immigrant narrative that had to be voiced on screen.

Seemingly Sisyphean Tasks

In 2014, we had the tremendous fortune of being supported by the Sundance Institute during the very early stages of the project, but it took another three years for the first money to come in. With the support of our Mexican producers at Panorama Global (Alberto Muffelmann and Gerardo Gatica), and Mexico’s EFICINE Film Stimulus Fund, production finally began in 2017, where the first half of the film was shot in Monterrey Mexico. Casting our principals was the first important “to-do” on our list, and with the guidance of our incredible casting director, Bernardo Velasco, we found the perfect group of teens to represent the film’s main ensemble: Los Terkos. After locking in our main cast, we had to contend with a city without any real filming infrastructure, as well as unpredictable weather. An incredible crew, pieced together from working professionals out of Mexico City and locals from Monterrey, helped us finish in mid-October 2017, but because of unforeseen overages, our team had to find finishing funds for the rest of the film. Simultaneously, we also had to figure out a way to have our lead actor, Juan Daniel “Derek” Treviño, travel and work in New York City during an unpredictable and hostile political climate.

While these issues forced us into a hiatus on the film, Fernando and I continued scouting in Jackson Heights, Queens to plan for the second half of the film. It was uncertain when things would resume, but visiting potential locations and meeting members of the community reconnected us with what had originally inspired us about the film. Hearing stories from undocumented immigrants and seeing how their experiences affirmed the themes in INLH gave us the energy to keep pushing forward.

The 11th Hour

To secure Derek’s work visa, we had a dedicated team of immigration lawyers at Milstein Law Group who organized our petition paperwork for him. They secured conditional approvals from Homeland Security to allow him to work in the US, but there was a final hurdle that Derek needed to clear, which was an in-person interview at the US Embassy in Mexico. Having never left his hometown of Monterrey, Derek was truly out of his element and was denied a visa after his first two attempts. Following his second interview, we were told that one of the reasons for Derek’s petition denial was that his estranged father had tried to illegally cross years earlier, and that reason was being used against Derek’s petition. It seemed incredibly unfair, but faced with a final interview attempt and the risk of jeopardizing US production, Panorama, Fernando and I called every contact that we had access to. I finally met with my Congresswoman’s office, Representative Yvette Clarke, who has one of the largest immigrant constituencies in the US. A signed letter from Rep. Clarke, along with a letter from IMCINE (federal agency that funds Mexican films) turned out to be the final pieces in getting us approval. Two months out from production, Derek was allowed to travel for the first time outside of Mexico.

In regards to financing, we used the footage we filmed in Mexico to craft a rough cut and trailer to attract additional financing partners. We also drew interest from a few distributors as well, and as our production window quickly approached in the late Spring of 2018, a potential deal with Netflix materialized. Miraculously, we were able to secure cash flow for the final leg of our production a couple weeks out from the start of production. During that same period, we received the news of being awarded SFFILM’s Rainin Grant, which capped a deluge of good news after a drought of uncertainty that made the film’s future feel anything but guaranteed.

Approaching the Finish Line

After wrapping production in the summer of 2018, Fernando and our editor, Yibran Asuad, spent the next year in the edit room, and later that fall, we began figuring out our film festival plan. After being shortlisted at several festivals, it took us another year to make our world premiere at the 2019 Morelia International Film Festival, where we won Best Film and the Audience Award. For Fernando, the cast, and crew, the awards were validation for all the hard work and sacrifice that was invested into the project, and it was especially moving to witness an incredibly emotional response from the first audience that saw the film at Morelia. The film went on to win several more prizes, including at Cairo International Film Festival, and landed on several top-ten lists in Mexico for 2019.

We were finally gaining momentum on the festival circuit before COVID-19 ravaged the global community, and one of the festivals we were looking forward to most was our US premiere at Tribeca Film Festival. This would have been a second homecoming for the film, but like all other spring festivals, Tribeca suspended its program, and thus sharing the film with our NYC cast and crew was put on hold. However, we are extraordinarily fortunate to release the film worldwide on Netflix, and we’re hoping to plan for multiple community screenings once theaters open up again.

As I have told Fernando and many of my colleagues, working on I’m No Longer Here has been one of the most challenging productions that I have ever been a part of. But it has also been the most rewarding film that I’ve ever been involved with, and I couldn’t be more proud of the incredible work that our team has done in telling such a profoundly humane story, one that feels so necessary during a time when so much inhumanity is being expressed by our political leaders. Films like this one are why I chose filmmaking as a profession since storytelling has the potential to equip artists with political agency, helping audiences foster a perspective outside of theirs, and ultimately, help bring more empathy into a world that desperately needs it.

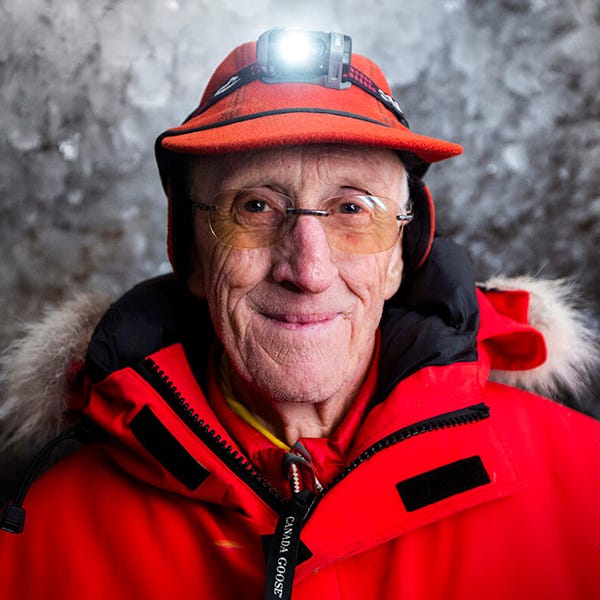

Gerry Kim is a Brooklyn-based producer whose previous films include Iris Shim’s The House of Suh (which premiered at the 2010 Hot Docs Film Festival and was sold to MSNBC Films), Jennifer Kroot’s To Be Takei, (2014 Sundance Film Festival premiere, released theatrically by Starz Digital) directors Esra Saydam and Nisan Dag’s Across the Sea (winner of the Audience Award at the 2015 Slamdance Film Festival, released on Amazon Prime), and The Untold Tales of Armistead Maupin, winner of the Audience Award at the 2017 SXSW Film Festival and distributed worldwide by Netflix. Kim also has helped produce long-form content for several companies, including Red Bull Music Academy and Mastercard. In 2014, was selected as a Creative Producing Fellow of the Sundance Institute for I’m No Longer Here, written and directed by Fernando Frias de la Parra. I’m No Longer Here won Best Film at Morelia International Film Festival, Cairo International Film Festival, Festival Internacional de Cinema de Tarragona, and Zacatecas International Film Festival. It was selected to screen at the 2020 Tribeca and San Francisco International Film Festivals, and has just been released worldwide on Netflix.

For more information about SFFILM’s artist development programs, visit sffilm.org/makers.