What is the SFFILM Youth FilmHouse Residency?

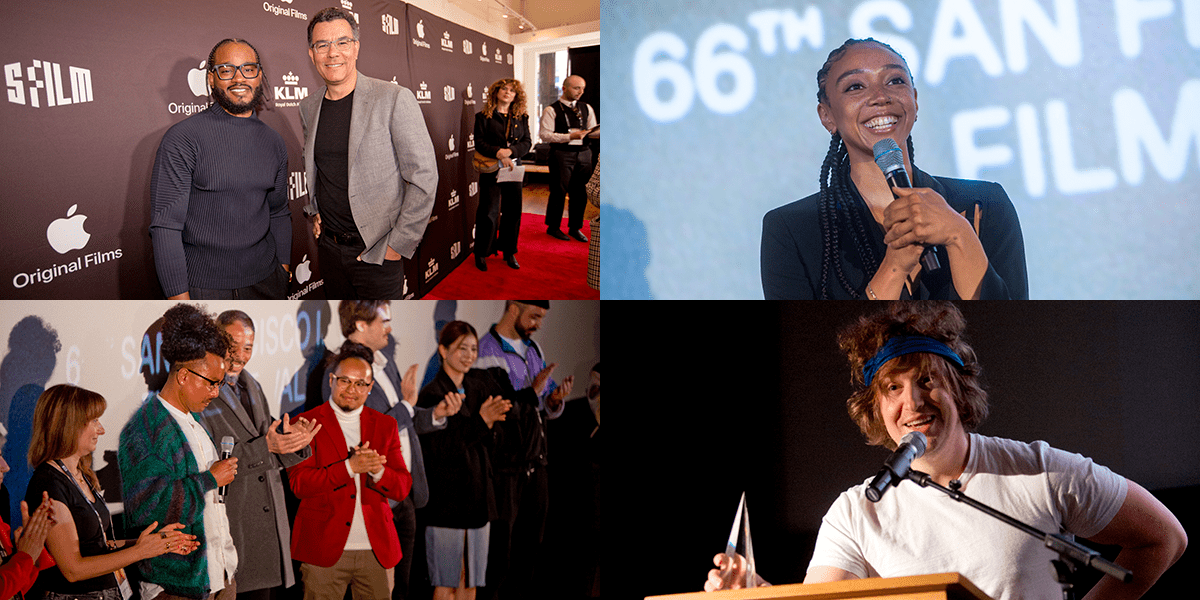

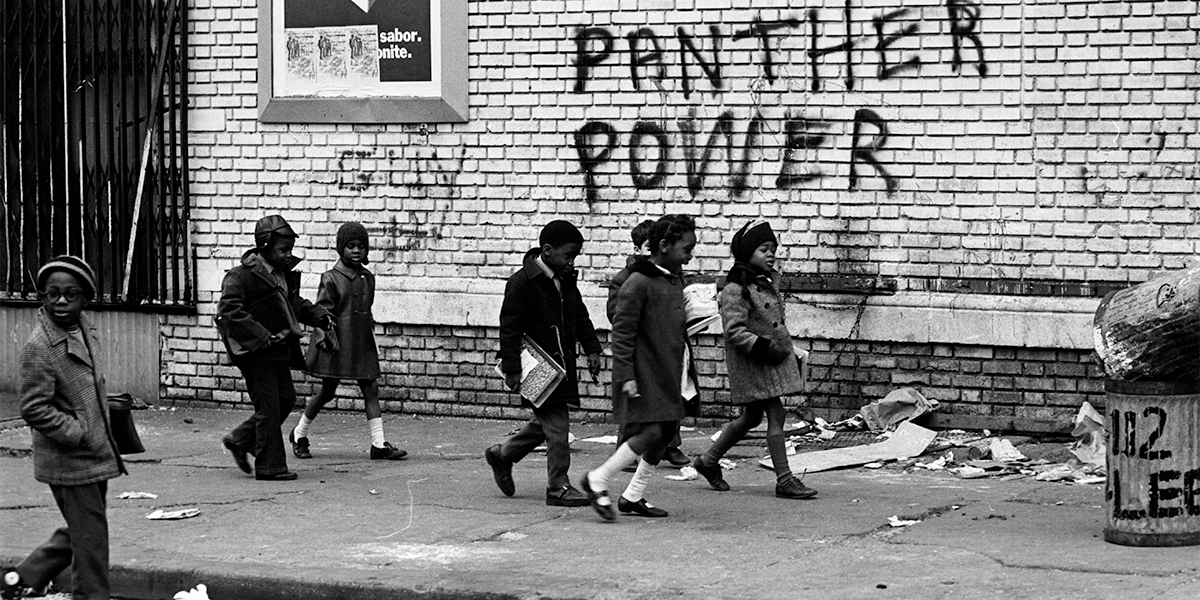

SFFILM Education’s Youth FilmHouse Residency, in partnership with SFFILM Makers, is an annual program that begins in the Fall semester for Bay Area students grades 9–12 who identify themselves as Black, Indigenous, or a Person of Color (BIPOC) and are excited to explore careers in film and filmmaking.

Throughout the residency, students will engage with other SFFILM residents, SFFILM staff, film industry professionals, and a dynamic curriculum that balances practical skills like production strategy and technique along with trainings, panels, and lectures that highlight industry knowledge and possible career paths through our artist network.

Do you know any students who would benefit from an experience like this? Our Youth FilmHouse Residency is now accepting applications for 2023. Sign up today!

Keep reading to meet the most recent group of Youth Residents for 2023.

2022 Youth FilmHouse Residents

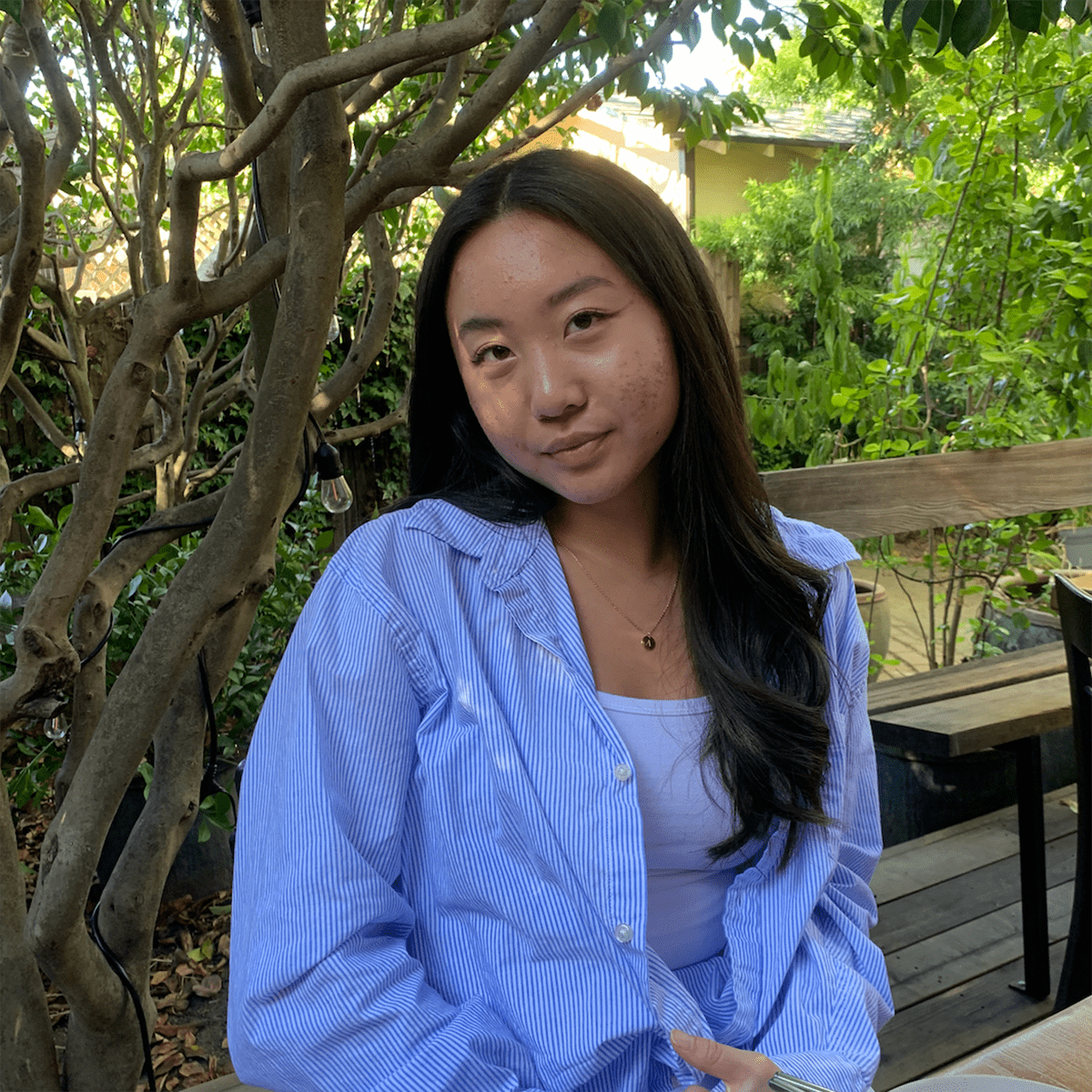

Annabelle Tong

My name is Annabelle and I’m a senior at Berkeley High School. I’ve been making films for about 3 years now and I plan to continue in college. The majority of my work is narrative but I hope to make documentaries in the future and one of my goals is to make music videos! I’ve been in a few film festivals so far and I’m currently in production for my newest project.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

I’m very inspired by my friends who make art in other forms, as well as other filmmakers of color.

Anything else you want to share with the public about your experience with the Youth FilmHouse Residency or about yourself?

The Youth FilmHouse Residency was so informative and such a cool experience, I got to meet so many other filmmakers and learn from their knowledge!

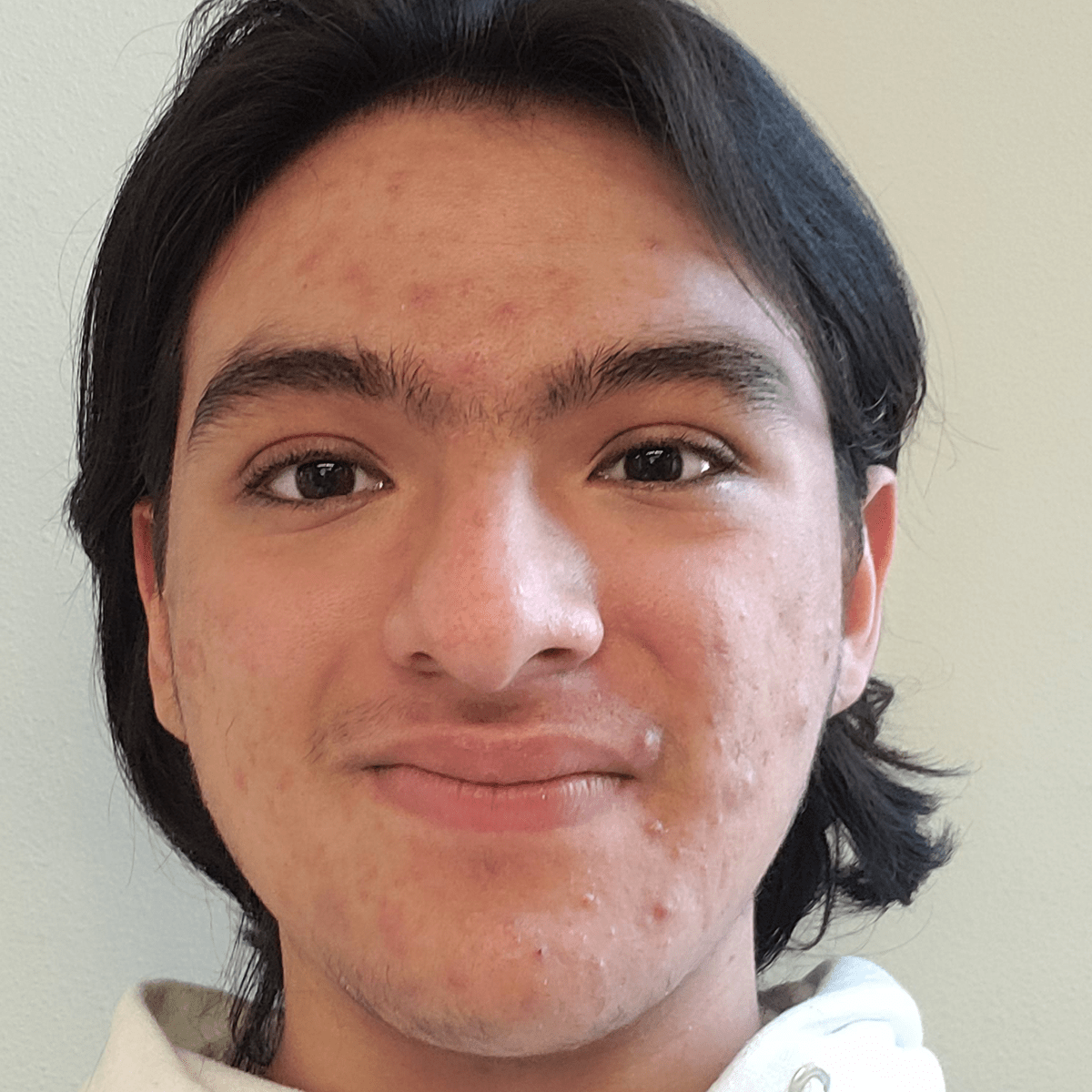

Diego Jaime

I am a Junior at Woodside High School and currently live in Redwood City. I plan on studying cultural anthropology and coupling that knowledge with my filmmaking experience to help me make documentary films. I am specifically interested in the connection between music and culture and how they influence one another.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

The ability to give a voice to those who may not have one is what inspires me to be a filmmaker. I am also influenced by movies like “Ornette Coleman: Made In America” that push the boundaries of what documentary films can look like and what they can achieve.

Emiliano Mejia

I am a senior at Phillip and Sala Burton High School. I live in Richmond but go to school in San Francisco. My first filmmaking experience was when I was in an internship where I helped make promotional videos for the summer internships the San Francisco Unified School District offers. I am currently working on a short film project for my arts, media, and entertainment class.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

My filmmaking idol is Cecelia Condit. I really admire how she is able to take disturbing and surreal fantasy stories with topics such as violence against women and aging to create amazing videos which have been described as feminist fairy tales. I also look up to her because of how she was able to take events from her life and put them into her stories.

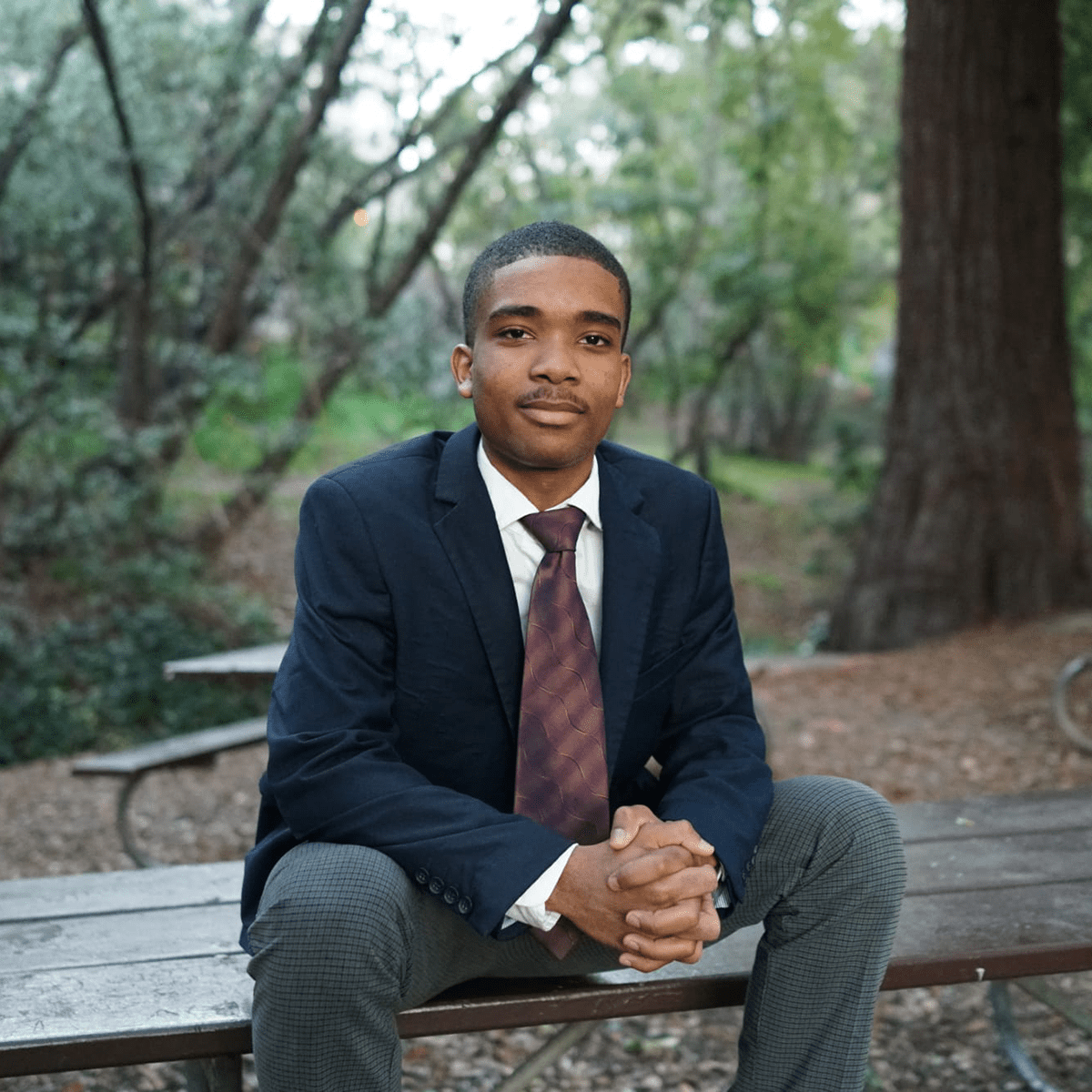

Jabreel Green

I’m Jabreel Green. I am in the 12th grade; I’m homeschooled, and I live in Berkeley. My Filmmaking experience is modest. So far, I have participated in 3 SFFILM youth filmmakers camps, I am currently an intern at B.C.M. and I have received a Certificate of training for Field Production, Media Journalism, and a Certificate of Appreciation from B.C.M. I also have two projects that are finalists In the Western Access Video Excellence awards. Right now I am working on a film that I’ve been working on for the past two years. I would love to share more once I’m past preproduction.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

What inspires me to be a filmmaker is the chance to tell a story that’s bigger than myself, a chance to create a world that I would live in, an opportunity to connect with characters that have the same problems as us, and a chance to reflect. I want to tell stories so my story can be told.

Kaiya Jordan

I’m Kaiya Jordan and I’m a junior at Berkeley High School. I hold a deep passion for film’s endless possibilities for creative and emotional expression and its ability to allow myself to showcase my perspective and world visually. My films typically incorporate aspects of experimental and narrative cinema, and I love working with combining different film mediums such as stop motion and live action! Passionate about film and art, I hope to pursue the industry in the future.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

My inspiration as a filmmaker comes from the stories I witness and hear about in my community, city, and people I choose to surround myself with. I’m inspired by the everyday dialogue of people I love and the scenery and landscapes I’m able to see.

Anything else you want to share with the public about your experience with the Youth FilmHouse Residency or about yourself?

The Youth FilmHouse Residency introduced me to the rich Bay Area community of filmmakers, and I’m so grateful I was able to meet and work with like minded young filmmakers!

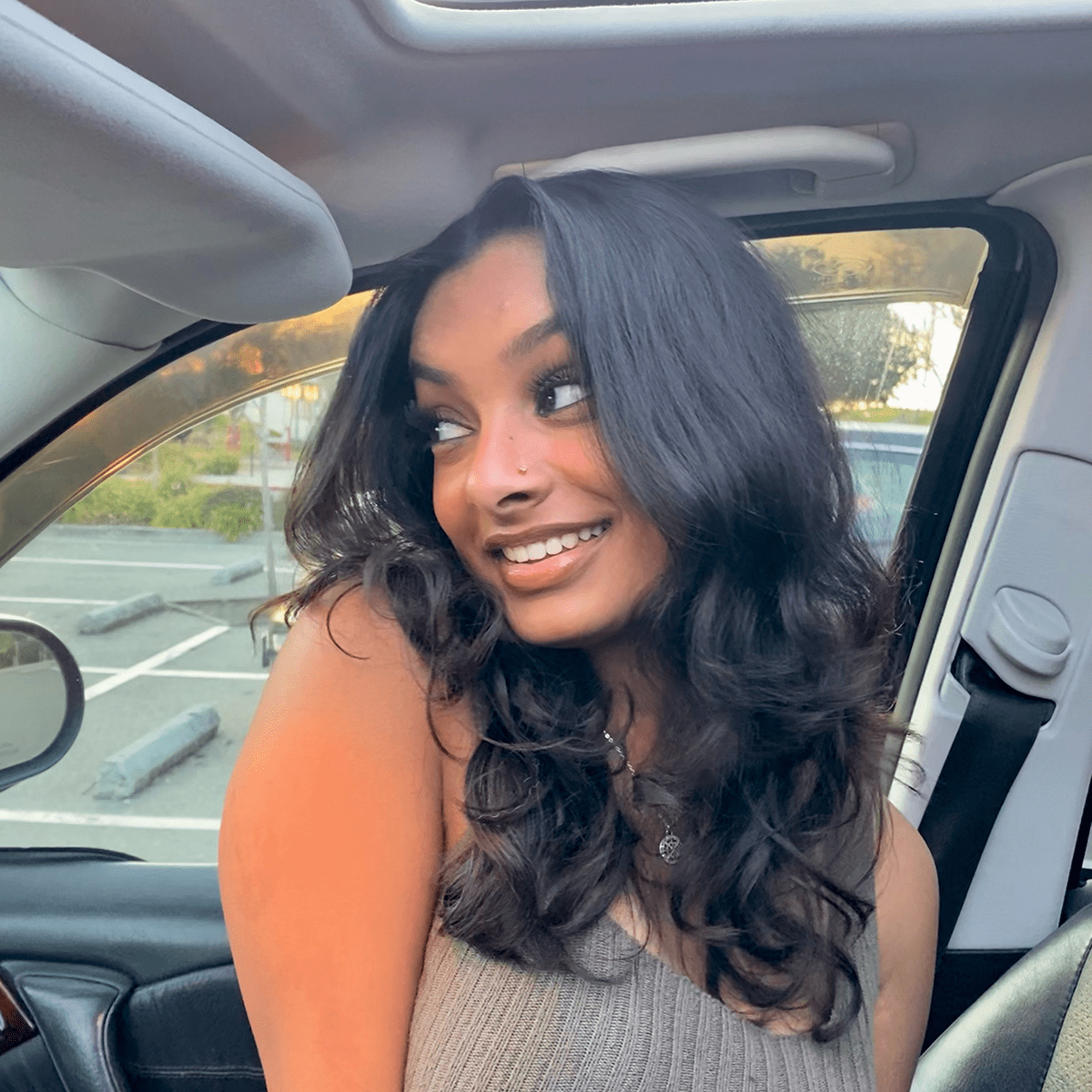

Keertana Sreekumar

Keertana Sreekumar is a 16-year-old filmmaker and English teacher. At age 15, she became the youngest screenwriter to win at Toronto Independent Film Festival for her feature screenplay, “The California Child’. This project is currently in development with filmmaker Vijaykumar Mirchandani. She is a co-writer on the upcoming online sitcom, ‘The New Normal’. She works as an assistant teacher at The Quarry Lane School. Keertana has managed 30+ artists through her management company, K. Productions, curating art gallery showings around the world.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

I grew up consuming art across mediums and demographics. I find inspiration for storytelling within Malayalam films of the 90’s, Latin Magical realism, Annie Ernaux’s memoirs, Indian classical music–the list is endless. My first screenplay, “The California Child”, was inspired by my high school experiences as a teenager with memory loss and a keen interest in hyperfixating on the culture I consumed.

Anything else you want to share with the public about your experience with the Youth FilmHouse Residency or about yourself?

SFFILM is one of the most welcoming creative spaces I have entered. Both Soph and Rosa have been incredibly supportive of our development as creatives!

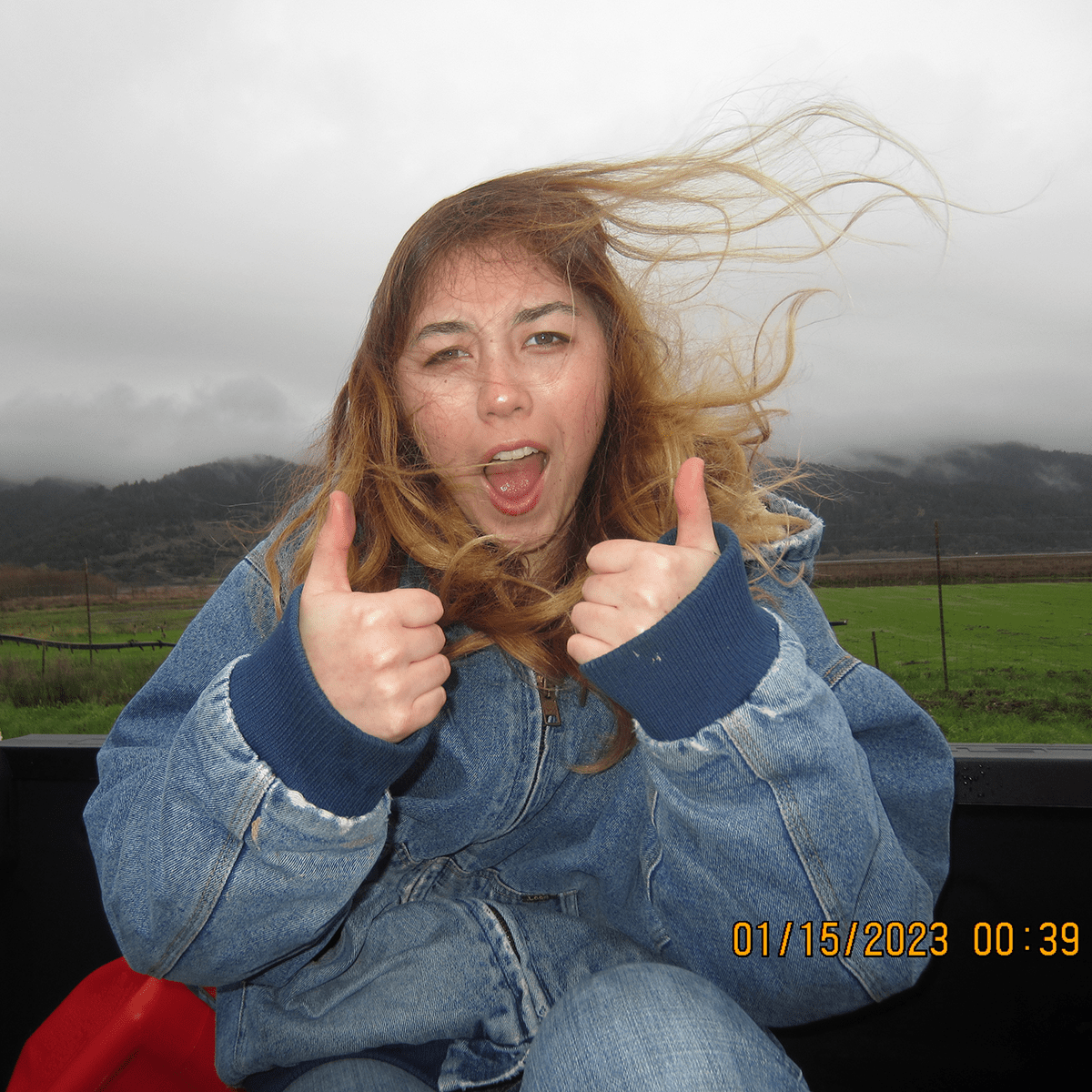

Kyla Burfoot

My name is Kyla Burfoot and I’m a Junior at Woodside High School. At Woodside I’ve taken the Digital Filmmaking, Digital Communications, and Advanced Digital Photography classes. These have all helped me advance my camera skills and over the years I’ve made quite a few school projects like music videos, broadcast packages, silent films, creative movies, and black and white. Currently I’m working on a broadcast package for KQED’s Youth Takeover, about hate crimes against Asian American and Pacific Islander elders. Thematically I tend to lean towards underdog stories, universal human experiences, and searching for beauty in the mundane.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

Wong Kar-Wai and Stanley Kubrick are two filmmakers who inspire me to be a filmmaker, with their breathtaking cinematography and beautiful storytelling. My family and friends also inspire me to make films because I love to capture the connections we have. Personal films about human experience impact me the most. Reading the news and hearing about current events also inspires me, because I feel drawn to spreading important stories to people.

Anything else you want to share with the public about your experience with the Youth FilmHouse Residency or about yourself?

I’m incredibly grateful for the Youth FilmHouse Residency experience. I loved working with the wonderful community of student filmmakers and adult filmmakers SFFILM works with. For anyone thinking of signing up–do it!

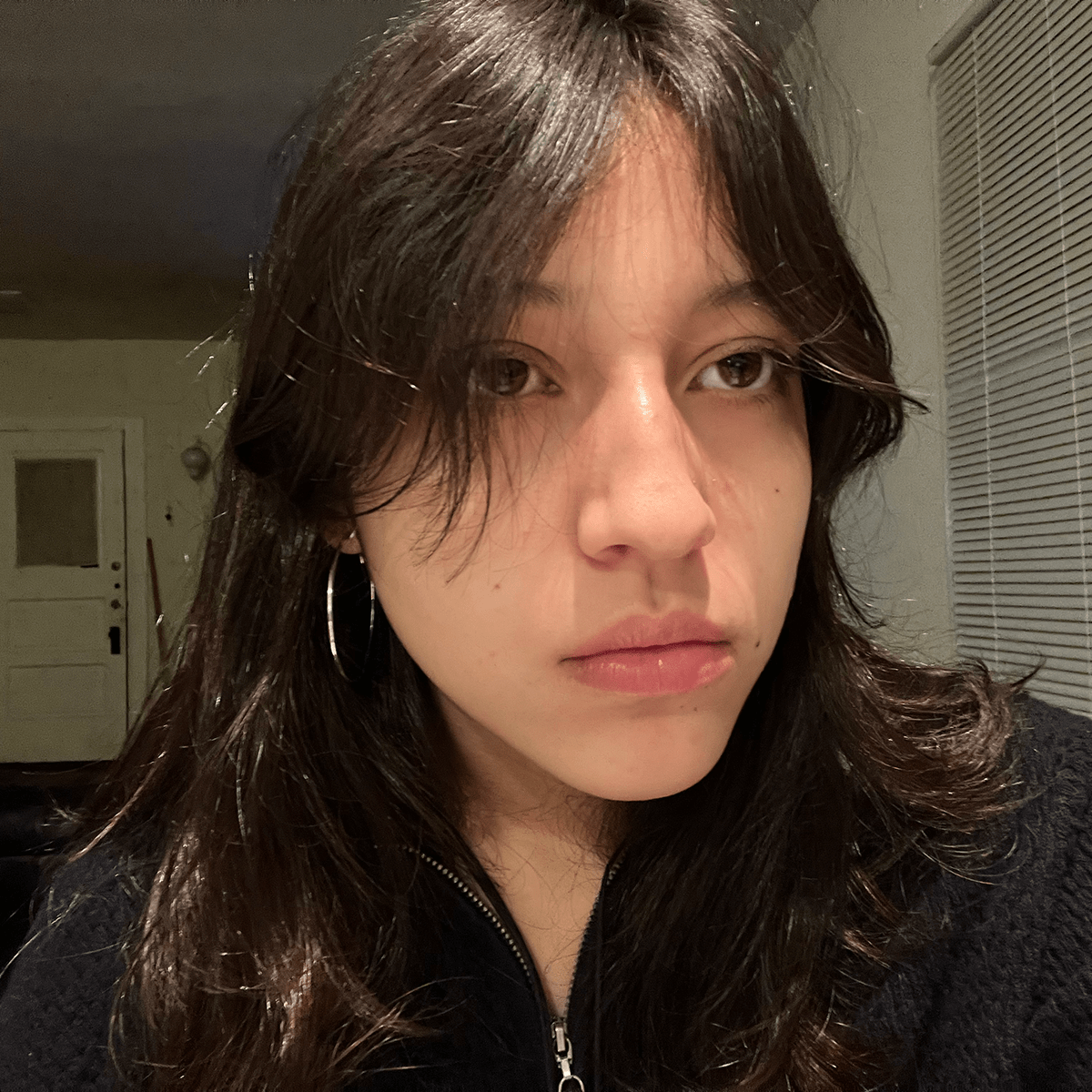

Monica Medina

My name is Monica I’m in 11th grade and go to Oakland School for the Arts. I live in San Leandro and I’m interested in narrative filmmaking. I’ve worked on a couple projects in the past with narratives and documentaries and hope to learn more about the film process.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

Cinematography really drives me in film making, how a single shot can convey so many emotions.

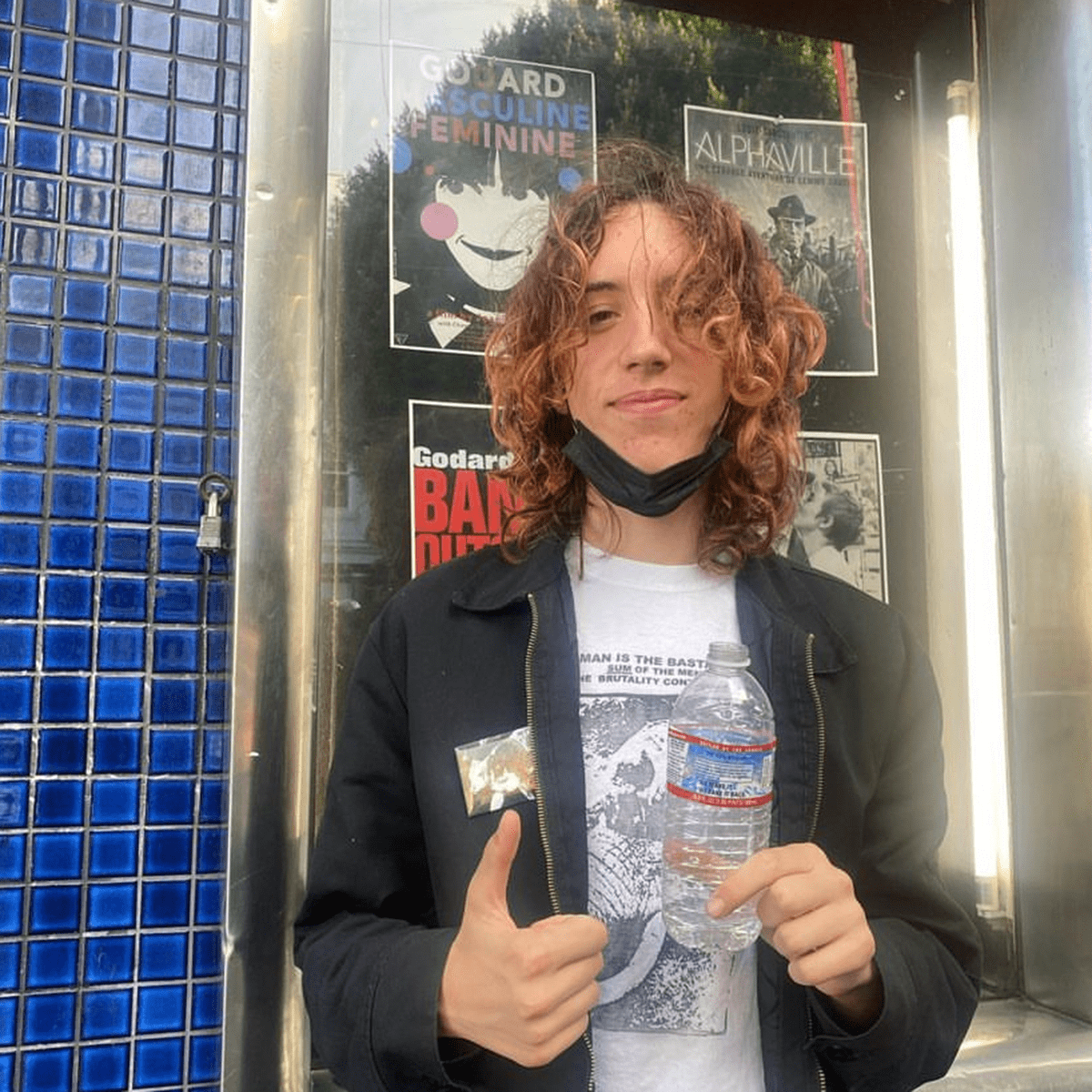

Santiago Avila-Green

My name is Santi. I’m 16 in my sophomore year of high school. I’m originally from Los Angeles but moved to Oakland in 2019 to be closer to family. I’ve been writing scripts for years and started acting as a little kid. My interests have evolved into writing more and more and directing/cinematography. I usually write narrative stories with a mix of sci-fi & drama. I am currently working on finishing my first feature length script.

Who or what inspires you to be a filmmaker?

Some inspirations that come to mind are Christopher Nolan, Michel Gondry, Greig Fraser, David Fincher and Tarantino.

Anything else you want to share with the public about your experience with the Youth FilmHouse Residency or about yourself?

I found it to be a very eye opening & important experience as I grow as a filmmaker.

Applications for Fall 2023 Residency Will Be Announced in the Summer. For more information visit here.

Stay In Touch With SFFILM

SFFILM is a nonprofit organization whose mission ensures independent voices in film are welcomed, heard, and given the resources to thrive. SFFILM works hard to bring the most exciting films and filmmakers to Bay Area movie lovers. To be the first to know what’s coming, sign up for our email alerts and watch your inbox.